You’ve just been shown a beautiful piece of land on the outskirts of Abuja. It’s fenced, well-situated, and the seller assures you the “papers are complete.” You’re tempted to act fast—after all, plots in the area are selling quickly.

But here’s the question: do you truly understand what it means to own land in Abuja?

Buying property in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT) isn’t the same as buying land in Lagos, Port Harcourt, or any other state. Here, the rules are different, the documentation stricter, and the legal stakes higher. We’ve seen well-meaning investors lose millions because they didn’t ask the right questions—or involve the right professionals.

At Kehinde & Partners, we’ve helped clients recover from near-disastrous land deals. And we’ve also helped others navigate the system smoothly from offer to ownership. This article is our way of sharing what we’ve learned: a practical guide to understanding how land ownership really works in Abuja, and how to protect yourself in the process.

Imagine being handed the keys to a house—only to discover later that the building stands on borrowed ground.

That’s the reality of land ownership in Abuja.

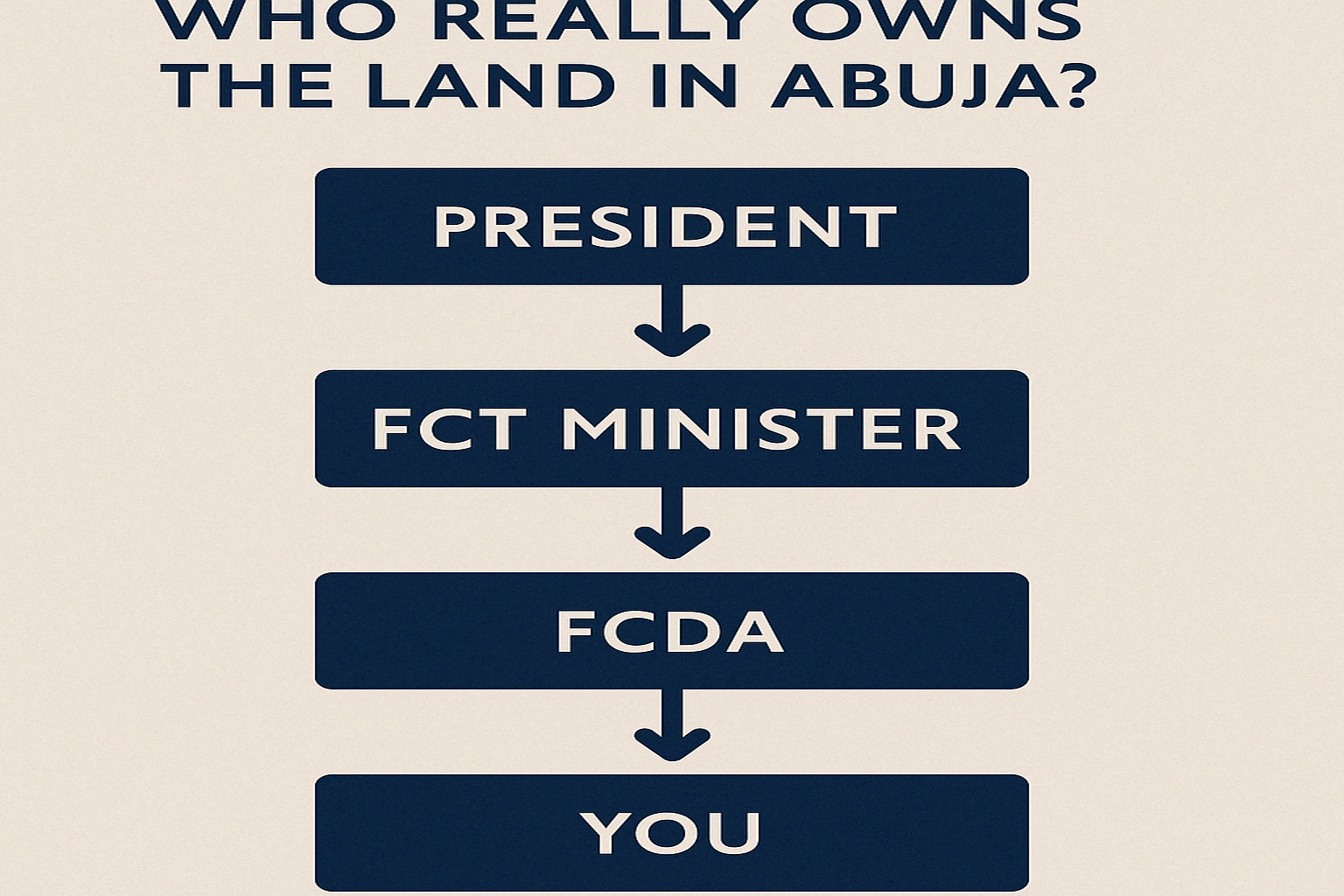

Under the Land Use Act of 1978, all land in Nigeria is technically owned by the government. But in the FCT, things go a step further: land is held in trust by the President and administered by the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) through the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA).

This means that when you “buy” land in Abuja, you’re not purchasing ownership in the traditional sense—you’re acquiring a leasehold interest, typically for 99 years, subject to government terms and approvals.

It’s like leasing a car from a company: you have rights to use it, develop it, even resell your interest in it—but the title stays with the issuer, and any violations of the terms (like non-compliance with zoning or development guidelines) can lead to revocation.

One client of ours, a business owner, purchased a large plot in the Jabi district through a private connection. The land was well-positioned for development, and everything looked legitimate—until she tried to register the property. She soon learned that the FCDA had no record of any allocation in her name. The title document she received? A forgery. Her investment? Frozen in litigation.

Moral of the story: In Abuja, land ownership begins and ends with the FCDA and the proper title process. Anything outside that system is a legal gamble.

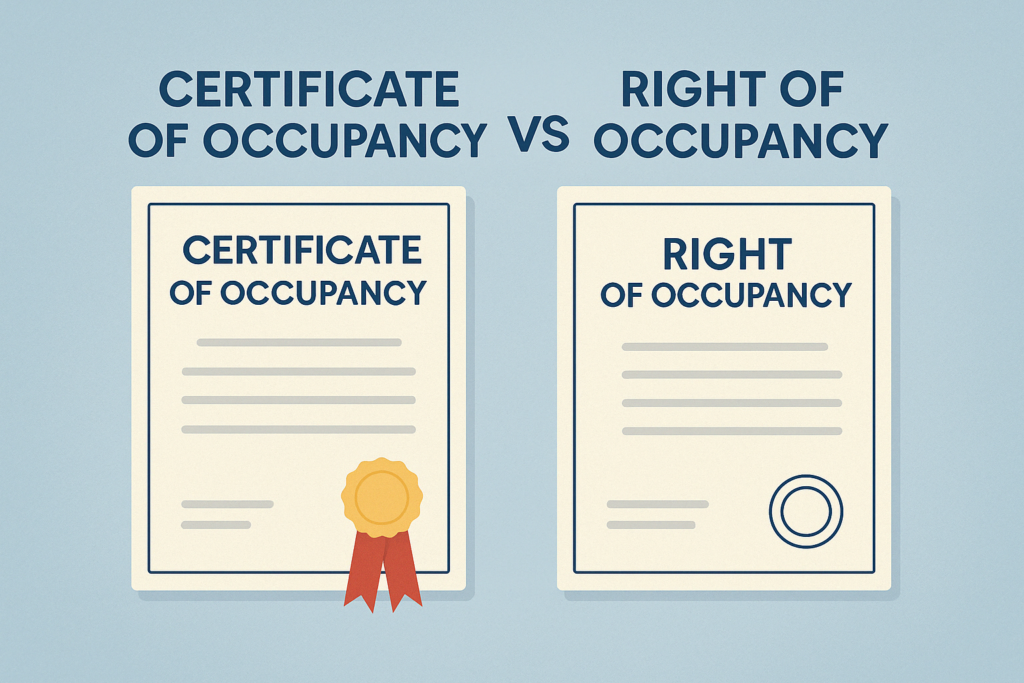

In Abuja, not all land titles are created equal.

To the untrained eye, a handwritten allocation letter from a village chief may seem just as valid as a stamped document from the FCDA. But in the legal world, especially within the FCT, that difference is the line between enforceable ownership and a ticking legal time bomb.

Let’s break it down.

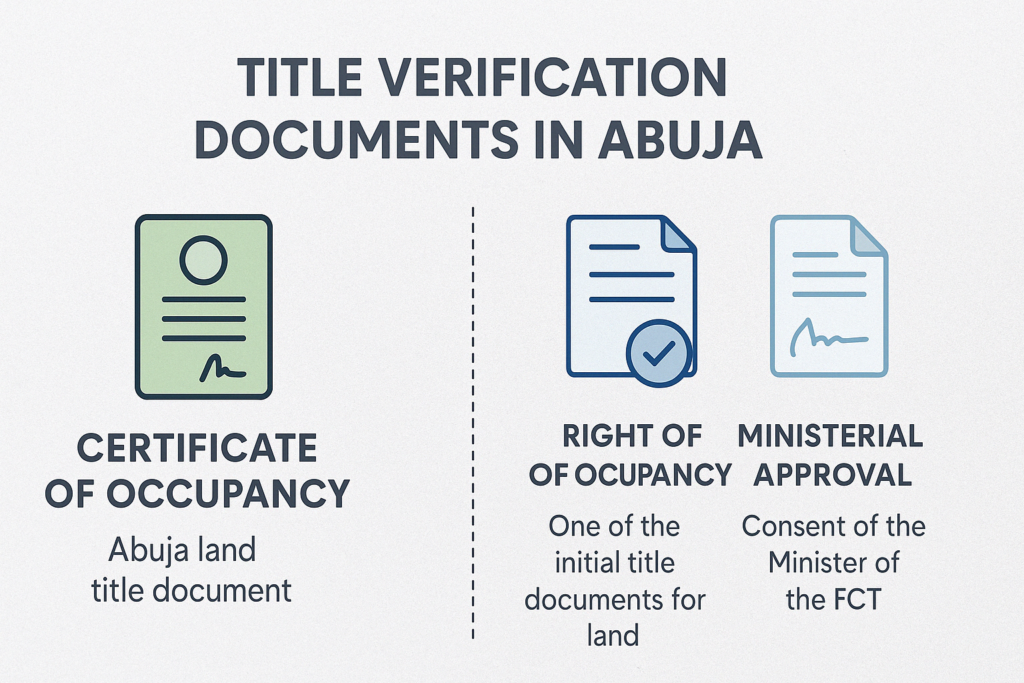

This is the recognized legal title in Abuja, issued by the FCT Minister through the FCDA. It gives you legal permission to use and develop the land for a fixed term—usually 99 years. It’s the title that AGIS (Abuja Geographic Information Systems) can verify. It can be registered, upgraded to a Certificate of Occupancy (C of O), and transferred.

If you’re buying urban land in Abuja and the seller doesn’t present a Statutory R of O (or a properly registered C of O), pause immediately.

Customary rights of occupancy are more common in states where local chiefs or families manage land allocation. They may work in rural Nigeria, but in Abuja, they hold little weight unless they’ve been formally converted through the FCDA.

We’ve seen too many cases where someone “buys” land through a local chief or community in places like Kuje or Gwagwalada, only to discover that the FCDA considers the land public reserve, commercial zone, or even earmarked for demolition.

A retired civil servant came to us after he “bought” three plots in Lugbe through a community representative. The price was attractive, and the documents looked legitimate—until he applied to AGIS for verification. Not only was the land unregistered, it had been allocated to a government housing project five years prior.

The money was gone, the land was lost, and legal redress was difficult—because the transaction was based on a non-statutory, unenforceable title.

Customary titles in Abuja are like street receipts—they might look official, but they won’t hold up in court or at AGIS. Statutory titles, on the other hand, are like certified cheques—verified, traceable, and protected.

If land in Abuja were a vehicle, these documents are your keys, license, and registration. Without them, you’re just sitting behind the wheel of a car you don’t legally own — and sooner or later, someone’s going to tow it away.

Let’s decode the most important legal documents every land buyer in Abuja should understand:

This is the gold standard of land ownership in Abuja. Issued by the FCT Minister, the C of O is proof that the government has granted you the legal right to occupy and use a specific piece of land. It’s a prerequisite for resale, development approval, obtaining building permits, or using the land as collateral.

Without a C of O, your ability to claim full rights over the land is severely limited.

Note: Many land buyers mistakenly believe that a signed sale agreement or a community allocation letter is enough. In Abuja, it’s not. Until you have a valid C of O, your title is considered incomplete.

The R of O is essentially a provisional form of tenure, often granted while a C of O is being processed or before formal documentation is completed. It gives you recognized control over land but is subject to further processing and approval.

In some cases, land is sold based on an “offer of R of O” — this can be acceptable, but only if verified through AGIS and legally transferable.

Certain land transactions — especially those involving resale, subdivision, or change of land use — require express approval from the FCT Minister. This ensures that the land’s new use complies with the Abuja Master Plan and zoning laws.

Skipping this step can lead to revocation, demolition, or court disputes, especially if the land is repurposed for commercial or high-rise development.

A client purchased a plot in Guzape, intending to develop a luxury apartment block. He paid in full, obtained an R of O, and began design planning. But when he applied for a development permit, he was informed the land had been zoned for low-density residential — and required ministerial approval for change of use. The process delayed construction by a full year and nearly cost him his investment deal.

Always request to see original copies of these documents — not just photocopies. Then, conduct a search at AGIS to verify their authenticity and current status (e.g., whether the title has been revoked, disputed, or mortgaged).

Buying land in Abuja without legal guidance is a bit like walking through a construction site blindfolded — every step you take could land you in trouble. Unfortunately, many buyers only realize this when it’s too late.

Let’s explore some of the most common legal traps we’ve seen — and how to avoid them.

Abuja has seen a sharp rise in fraudulent land deals. Scammers target eager buyers with forged allocation letters, fake survey plans, or even duplicate sales of the same plot.

Case Example: A business owner paid ₦20 million for two plots in Karshi. He was shown signed letters and even taken to AGIS — but it turned out the seller was impersonating the real owner. By the time legal action began, the fraudster had vanished and the real owner had resold the land.

How to avoid it:

Abuja operates under a strict Master Plan managed by the FCDA. This means every district and plot is zoned — residential, commercial, industrial, greenbelt, etc.

We’ve handled cases where buyers unknowingly built a shopping complex on residential land or attempted to construct a duplex on greenbelt land — only to face demolition orders and huge financial losses.

How to avoid it:

This is one of the most dangerous pitfalls. Sophisticated forgeries can fool even seasoned agents — from counterfeit FCDA stamps to forged survey plans and cloned C of Os.

Red flags to watch for:

Analogy: “Buying land without verifying the title is like wiring money to someone you’ve only spoken to on WhatsApp — if it goes wrong, proving your case becomes a nightmare.”

In Abuja’s real estate market, confidence doesn’t come from what the seller says — it comes from what the law confirms.

Whether you’re purchasing a single plot or partnering in a multimillion-naira estate development, the most valuable investment you can make is legal due diligence. And in our experience, the buyers who lose money are usually those who skipped it.

Think of your lawyer not as a document handler, but as your strategic shield.

At Kehinde & Partners, we’ve helped clients uncover issues such as:

- Hidden liens (the land was collateral in a loan)

- Ongoing litigation on the property

- Unauthorized subdivisions or encroachments

- Misrepresented land use classification

When to involve your lawyer:

Before you pay a deposit

Before you sign an MoU or agreement

Before you act on any verbal assurances

AGIS (Abuja Geographic Information Systems) is the legal backbone of Abuja land verification. A title search will reveal:

Don’t skip this.

Even the most professional-looking documents can be worthless without confirmation from AGIS.

Whether it’s a joint venture, lease, purchase agreement, or land contribution deal — the contract must clearly define:

Story: A group of siblings inherited ancestral land in Gwagwalada and agreed to partner with a developer. But there was no legal agreement in place. Two years later, the developer sold off parts of the land — and the family couldn’t prove breach. Kehinde & Partners was engaged only after the damage had been done.

If you’re buying from an existing holder of a C of O or engaging in certain types of land transfers, Ministerial Consent is mandatory. Transactions without it can be nullified — even years later

Ready to move forward with confidence? Let Kehinde & Partners help you verify titles, navigate land laws, and safeguard your real estate investments.

Book a Consultation Now